Hosannar!

One of the most popular Christmas carols (songs) is Ding Dong Merrily On High. It’s an old French tune

One of the most popular Christmas carols (songs) is Ding Dong Merrily On High. It’s an old French tune

which was published in 1924 with English lyrics:

Ding dong merrily on high,

In heav’n the bells are ringing:

Ding dong! verily the sky

Is riv’n with angel singing.

Gloria, Hosanna in excelsis!

The Latin in excelsis is translated as ‘in the highest’ (in heaven). Hosanna comes from Hebrew and is an exclamation of praise; English speakers pronounce it with the same final vowel that they use in sofa, extra, America, etc., namely the little colourless vowel ‘schwa’, symbolized /ə/.

When such words are followed by a vowel in the next word, a connecting /r/ is often added by speakers in England, Wales, Australia and New Zealand (and by some in the USA, like Bernie Sanders). This is especially likely in frequent word combinations where the following vowel is unstressed, e.g. Obama/r/administration, Pizza/r/Express, Honda/r/Accord – and, given the carol’s popularity, hosanna/r/in excelsis. Every Christmas it can be widely heard in England:

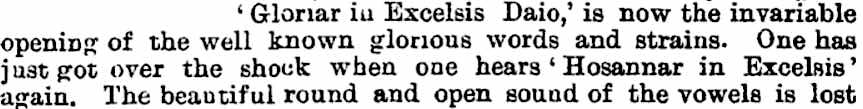

The added /r/ is an example of the way in which languages sometimes try to avoid sequences of vowels (languages prefer consonants and vowels to alternate); and it’s been around quite a long time. Here’s a New Zealand writer mentioning it in 1899:  That writer didn’t like the added /r/. It’s long been condemned as ‘intrusive’, although it’s used by speakers of all social classes and educational levels. Many choral directors train their choirs not to sing hosanna/r/in excelsis, but without such training choirs in England etc. will naturally tend to sing it that way.

That writer didn’t like the added /r/. It’s long been condemned as ‘intrusive’, although it’s used by speakers of all social classes and educational levels. Many choral directors train their choirs not to sing hosanna/r/in excelsis, but without such training choirs in England etc. will naturally tend to sing it that way.

Should non-natives avoid this kind of /r/ in their spoken English? The individuals I know who’ve got closest to a native-sounding British accent do tend to use it. I myself stopped using it, not because I disapprove of it but because of years spent living in the USA and Scotland, where I tended to ‘accommodate’ my pronunciation to the locals. But for most non-native users of English, the question of avoidance is really immaterial, because their speech is so dominated by writing that they’re very unlikely to say a consonant that isn’t written.

(You can hear many more examples of linking /r/ in this longer and more technical article.)

Words of the Week is taking a break until the New Year. A happy and peaceful holiday season to all my readers!

The letter-writer’s spelling ‘Daio’ indicates that he disapproved of using the continental vowel in that word. So do I; I have never stopped thinking the Latin phrases in English should be given the English pronunciation sanctioned by immemorial tradition. That Italian ‘ch’ in ‘excelsis’ is like a sore thumb in the works; and I can’t imagine saying, or wanting to say, e.g. ‘Nemo me impune lacessit’ with other than the full Anglicisation /ˈnimo mi ɪmˈpjuni ləˈsɛsɪt/, but I fear I would not be understood. I suppose my ‘deity’ (English vowel) to be strange, as well, but it’s still understood here. In sum the treatment of Latin phrases in English today is deplorable.

If you personally have eliminate intrusive R from your speech, as you suggest, it means that you have unmerged several phonemes. This is far from impossible, with practice. My own example is that I was born with the cot/caught merger (PALM/LOT = THOUGHT = [ɑ] probably) but have unmerged them so completely that I can’t even imagine speaking the old way anymore, and can’t help see on/gone as a terrible rhyme.

k_over_hbarc at yahoo dot com