STRUT ʌ, schwa ə and American English

Over the years I’ve occasionally been approached, say after giving a talk, by an American clutching a dictionary, who tells me they “just have one question”. It’s usually the same question: what is the difference between ʌ and ə?

There’s a lot of confusion about ʌ and ə in American English. It’s easy to find online, on Q&A sites and in YouTube videos by well-intentioned tutors. My own latest video begins with a compilation of clips in which various attempts are made to explain the ʌ/ə issue, in terms of length, pitch, loudness, laziness etc. The main points of agreement seem to be: 1. Americans must know and use both symbols, 2. schwa must never, ever, under any circumstances be stressed.

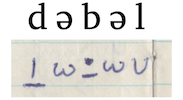

As I go on to explain in the video, I totally empathize with the confusion, because I went through it myself as an undergraduate student. Like most Americans, I myself have a native accent with one vowel phoneme that occurs in both syllables of words like above, Russia, luscious, fungus and double.

I’m from Merseyside, the Liverpool area. Although English northerners are famous for pronouncing STRUT words like run, cup, and love with the FOOT vowel, many other northerners pronounce such words with schwa, and that’s my native system. (My next video will look at the range accents that do the same thing.)

There’s no doubt about my only having one vowel here. When I was 13, I invented my own phonemic alphabet, without the help of any books, guided only by my intuitions. I definitely used the same symbol for the two vowels in double, and for the underlined vowels in Young Winston. So a few years later when I arrived at University College London and encountered the phonemes of RP (Received Pronunciation), I was at first surprised and confused by a distinction between something written /ʌ/ and something written /ə/. To transcribe RP, I needed to work out when to use these two different symbols. And this is the position many confused Americans find themselves in.

So a few years later when I arrived at University College London and encountered the phonemes of RP (Received Pronunciation), I was at first surprised and confused by a distinction between something written /ʌ/ and something written /ə/. To transcribe RP, I needed to work out when to use these two different symbols. And this is the position many confused Americans find themselves in.

But Americans aren’t transcribing RP! So why do they feel they need to write two phonemes, when their accent, like mine, has only one?

It’s because numerous influential resources transcribe AmE with exactly the same /ʌ/ and /ə/ symbols that are used for RP, or contemporary SSB. These resources include the two best known pronunciation dictionaries, the Longman Pronunciation Dictionary and the Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary. But neither of these explain why they show an ʌ-ə contrast for AmE. At least the Longman admits what it’s doing:

LPD distinguishes between the vowels ʌ and ə, although in American English they can generally be regarded as allophones of the same phoneme.

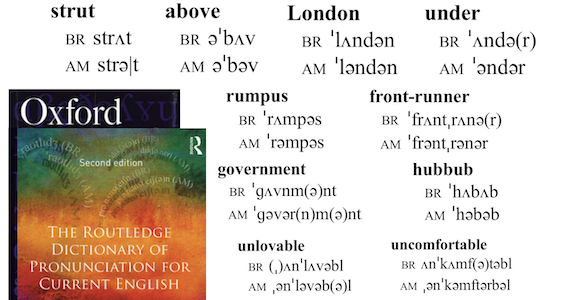

I’ll get to the possible reason for their decision in a moment. First I want to point out that there are many important resources which show the single American schwa phoneme for what it is, and completely do without /ʌ/. These include:

• the Merriam-Webster Collegiate Dictionary, “America’s best-selling dictionary”, available online at merriam-webster.com

• lexico.com, from Oxford Dictionaries

• Google translate

• the Oxford Dictionary of Pronunciation for Current English, now the Routledge Dictionary in its 2nd edition

• American English Phonetics and Pronunciation Practice, by Carley and Mees

• American English Phonetic Transcription, also by Carley and Mees

This isn’t some new thing, by the way. For example, the single /ə/ phoneme is used in 1957’s classic An Outline of English Structure by Trager and Smith.

This isn’t some new thing, by the way. For example, the single /ə/ phoneme is used in 1957’s classic An Outline of English Structure by Trager and Smith. (Even the dictionary I co-edit, CUBE, though we’re not quite ready to release our American version, has an option to display just one phoneme rather than two.)

(Even the dictionary I co-edit, CUBE, though we’re not quite ready to release our American version, has an option to display just one phoneme rather than two.)

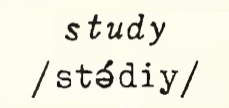

So back to the question, why is it that some resources feel a need to phonemically misrepresent General American? I think an important factor is a desire to maintain a dogma that “schwa is never stressed”… even though it widely is.

As I said before, I’ve been through all this myself, as a student. If you’re trying to transcribe RP and you have /ə/ but not /ʌ/, you have to remember the rule: write it with a schwa symbol when it’s unstressed, but write it /ʌ/ when it’s stressed. And this is the exquisite irony: it’s those of us who do stress schwa who cling most pathetically to the rule that it isn’t stressed, because it means you can transcribe RP without having to look every ə/ʌ word up in a dictionary.

But, sooner or later, this strategy is bound to go wrong. In the video, I show a clip of an American YouTuber insisting that the word undone is /əndʌn/. Of course it isn’t: for those with a STRUT-commA contrast, it’s /ʌndʌn/. The YouTuber is aware of the stress difference between the two syllables and has been led to believe that stress differences require him to write different symbols. So he makes this mistake precisely because he stresses schwa every day of his life! It’s the insistence by various resources on two symbols for American English that causes so much mystification.

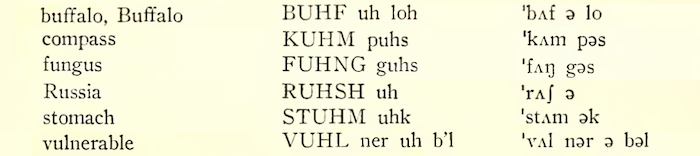

Note by the way that when Americans show pronunciation by means of respelling, as they very often do, they feel no obligation to show a difference, using “uh” for both their stressed and their unstressed schwa. Here’s the old NBC handbook of pronunciation.  In re-spelling, it puts “uh” in stressed and unstressed syllables. It’s only in IPA that it has to pretend there’s two phonemes. Which suggests that, for many people, the unstressable-schwa dogma isn’t even about speech: it’s just a typographical commandment about where one can print a particular visual symbol, ə.

In re-spelling, it puts “uh” in stressed and unstressed syllables. It’s only in IPA that it has to pretend there’s two phonemes. Which suggests that, for many people, the unstressable-schwa dogma isn’t even about speech: it’s just a typographical commandment about where one can print a particular visual symbol, ə.

The dogma is astonishingly entrenched beyond specialist phonetics:

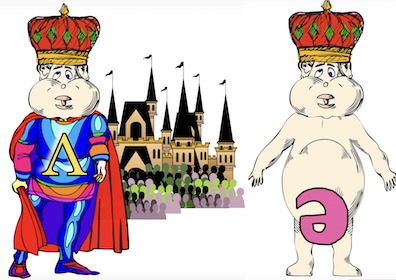

And academic linguists face the dilemma of how to deal with all the facts that contradict the dogma. The dilemma is articulated beautifully in English Accents & Dialects by Hughes, Trudgill and Watt. The authors describe a range of English accents which, like mine, have stressed schwa, and then wonder how they can reconcile the evidence with the dogma on all those T-shirts, face masks and tote bags.

given that one of the conventional defining properties of /ə/ in English is that it occurs only in unstressed syllables, it might be best to view [ə] in stressed syllables as a realisation of /ʌ/ that is neutralised with respect to unstressed schwa.

This sounds to me slightly dishonest, or delusional. To paraphrase…

given that one of the conventional defining properties of the Emperor is that he’s nude only in private,

it might be best to view the Emperor in public as wearing a suit of lovely clothes that is neutralised with respect to total nudity.

As the authors say, it might be best to do that. And then again it might not.

As the authors say, it might be best to do that. And then again it might not.

Extrapolating from ‘schwa is unstressable in RP’ to ‘schwa is unstressable in English (and beyond)’ is simply an error. There’s nothing on the IPA vowel chart that says any of the vowels are unstressable. Nor would it make any sense to have two sets of vowel symbols, one for stressed syllables and one for unstressed syllables. And dictionaries don’t generally show allophones (variants) of a given phoneme: they use the same symbol for the two different /l/s in illegal, and the same symbol for three very different /t/s in treatment.

Now, across languages, we sometimes find phonological systems that have some kind of typically central vowel that’s the result of processes of reduction or epenthesis, or is in some way restricted to weak prosodic positions. We can find this kind of restricted vowel in French, German, and some accents of English, including SSB. I can understand that phonologists want a label for this phenomenon, but I don’t see how they can have exclusive rights to the name “schwa”, because all over the world that word is indelibly associated with the symbol /ə/. And that symbol means a mid central unrounded vowel that’s just as stressable as any other vowel (and which is stressed by a wider range of English speakers around the world than those who can’t stress it; more in my next video).

So, Americans: if you’re an English pronunciation teacher, you may want to suggest a more open articulation when schwa is stressed; and if you’re a dialect specialist, of course you’re going to want to learn a wide range of symbols and exactly what they all mean. But for most ordinary people, phonemes are more than enough. And most Americans, as far as I’m aware, have one STRUT/commA phoneme which, despite the dogma splashed all over the merch, occurs in both unstressed and stressed syllables.

Thank you so much for this post. I greatly appreciate your ability to unpack some of the confusing conventions associated with traditional transcriptions and explain how an accent actually differs from the manner in which it’s transcribed. As an American, I’m especially interested to see a post that relates to my variety of English more than most of the content on this British-focused blog. And I find the matter of STRUT vs. schwa and knowing when to write each symbol even more confusing, for reasons I’ll explain in a moment.

I’m a film major without any formal training in phonetics, but I believe that many Americans have an additional central unstressed vowel that complicates matters somewhat. This forces me to disagree slightly with the statement that “Americans have only one STRUT/commA phoneme.” I do indeed have the same phoneme in both those words, which I’m going to symbolize as [ɐ] rather than schwa or [ʌ] to minimize the confusion created by the traditional transcription and to be more phonetically accurate. However, not all Americans use the same phoneme both in all words conventionally transcribed with STRUT and in all words traditionally transcribed with schwa.

Judging by this paper (http://web.mit.edu/flemming/www/paper/rosasroses.pdf), many if not most Americans have both a morpheme-final reduced central vowel (which for me is identical with STRUT, and which I would transcribe as [ɐ] as explained above) and a non-morpheme-final central reduced vowel with a higher tongue position, which the authors of the paper I linked transcribe as [ɨ]. For me, the non-final reduced vowel is an allophone of KIT (I also have the inaptly named “weak vowel merger,” as do many other Americans, so pairs such as Lennon/Lenin are the same and abbot/rabbit rhyme). The contrast between the two reduced central vowels is probably the result of an allophonic split that has become sensitive to the morpheme boundary, as with the distinction found in parts of Ireland between “tenor” and “tenner”, or the London distinction between “board” and “bored.”

Crucially, however (in my near-GenAm idiolect at least), the weak KIT vowel merged with the higher reduced vowel after the split, while STRUT merged with the lower reduced vowel. The result is something like the correspondences of PALM, LOT, CLOTH, and THOUGHT in most varieties of British and American English; we have two phonemes (though many have merged them down to just one) where Brits have three phonemes for the same lexical sets. Essentially, the historic /ɒ/ phoneme has split, and most instances have merged with PALM, while many other instances have merged with THOUGHT. In the same way, AmE schwa has split, with one of its products merging with unstressed KIT, while the other has merged with STRUT.

As you can imagine, this makes the traditional transcriptions incredibly ill-suited to AmE; a distinction made by many Americans is not indicated in transcription, while two distinctions that don’t exist for many Americans are often indicated. This gave me no end of confusion when I looked at the pronunciation key of a dictionary as a child (the third edition of the American Heritage College Dictionary) and saw that three different symbols were used for what I would later learn were weak KIT, STRUT, and schwa. The schwa was listed with both the first vowel in “about” and the second vowel in “circus” as keywords, which made no sense to me because I didn’t have the same vowel in both those words. At the same time, the vowel I used in about was identical to the one in “cut,” which was given a different symbol!

Obviously, this is not the time or the place to suggest a wholesale revision of GenAm transcriptions in the same manner as for SSB. However, I would like to see dictionaries using transcriptions that align more closely with the phonemic distinctions that Americans actually make instead of holding onto outdated transcriptions. I’d also like to see symbols used that more closely reflect the phonetic value of some GenAm phonemes. The GOAT vowel, for instance, rarely has a fully back start (except before [ɫ])—and to use such a vowel now sounds old-fashioned. You can hear the earlier form of the diphthong in the words “own” and “road” at around 2:10 in this 1950 Disney cartoon (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mwPSIb3kt_4); they definitely don’t sound the way most Americans pronounce them today. And I can’t understand why the American /ɹ/ is transcribed as alveolar, postalveolar, or retroflex. It may have those articulations in other varieties of English, but if I look in a mirror while saying a word such as “arc” with my mouth open enough to see inside, my tongue moves slightly upward and forward from the /ɹ/ to the /k/, which suggests that my /ɹ/ would be better described as velar (or post-velar after back vowels), not alveolar or retroflex. My /ɹ/ has virtually the same articulation in all positions, and the tip of my tongue is not raised, let alone retroflex. But I digress.

I haven’t meant to invalidate anything you explained in your post. I have definitely heard Americans who have no such distinction between lower and higher reduced central vowels, but it seems that a substantial number, perhaps the majority, do have this distinction. This is how we do distinguish roses (with [ɨ]) from Rosa’s (with [ɐ]) but don’t distinguish rabbit/abbot or Lenin/Lennon. I haven’t seen much literature on the subject that actually explains this situation, though; most seem to believe that Americans have the same weak vowel system as either Brits or Australians (with the addition of a rhotic lettER vowel), rather than acknowledging that a substantial proportion of us appear to have quite a different system.

Even for speakers who make this distinction, everything in your post remains valid. I don’t understand why Americans have to keep writing STRUT and schwa as distinct when many instances of the two have merged, and I also don’t see why those of us who merge our higher central reduced vowel with KIT can’t write it as such. I absolutely support your efforts to clarify the mess of conventions that have led to this situation and would also like to see each variety of English written with a transcription that is phonetically and phonologically accurate.

Unfortunately, it seems that the italics I included when writing this disappeared when I pasted it into the response box. I’ve added some quotation marks to clarify the post where necessary.

Hi Chris, and many thanks for the thoughtful comments, which are pretty sophisticated for a phonetics ‘amateur’!

Your point about KIT is the one that’s come up the most in comments from Americans on YouTube. I was about to include it in the video and left it out as I try to keep the length and complexity manageable. Basically the approach I took was to say ‘Hey guys, if you’re confused by ʌ and ə in so many resources, you can find just ə in a bunch of other resources.’

The difference between the ‘Rosa’s’ vowel and the ‘roses’ vowel used to be typically described as schwa allophony, i.e. /ə/ having two conditioned allophones, [ə] and [ɨ]. However, over the years I’ve increasingly found Americans intuiting the latter to be an allophone of KIT. I don’t know if this reflects an actual change, like the way many younger speakers on both sides of the Atlantic have reanalysed the phonetic affricates in ‘try’ and ‘dry’ as /tʃr/ and /dʒr/, rather than the /tr/ and /dr/ that old folks like me feel them to be. (Do you have /tʃr/ and /dʒr/?) I mention the latter change because it’s yet another widespread phenomenon that the standard dictionaries and texts have simply ignored. (And yes, I know we don’t have it in CUBE either, but at least we’re working on doing so.)

The KIT intuition is reflected in American forms like Eminem, Linkin Park and Mickie D’s. I originally had no idea that Eminem and Linkin related to M & M and Lincoln, because those for me are M/ən/M and Link/ən/. Mickie D’s was obvious from context, but for me it’s M/ə/cDonald’s.

The solution, of course, is simple: Ros/əz/ and ros/ɪz/, John and Vladimir Len/ɪn/, the abb/ət/ has a rabb/ət/, or whatever is appropriate to the accent in question. I’ll revise this article to mention it, and when I have a moment I’ll maybe add a little supplementary video to YouTube.

Lastly, I think you’re talking about bunched tongue r? Maybe have a look at my article called ‘Vodka martini, bunched not curled’ or something like that.

Thanks! As I suggested, I think that at one time the AmE schwa allophony may solely have been conditioned by the context (and the difference between the two forms may have been less obvious than today). But once the higher version of schwa merged into weak KIT and the lower version merged with STRUT, the distinction became more fully contrastive. The truth is that at this point, we should probably consider (some kinds of) BrE to have an additional weak vowel that Americans don’t, since the schwa has split and merged with either KIT or STRUT in AmE. Thus, American English is actually more regular in its weak vowel system than “RP” and similar accents, even though the transcriptions make it look less regular. To answer your question, then, I think it does reflect an actual change—a merger. I don’t know, though, whether that system of splits and mergers is anything new. I remember watching The Wizard of Oz recently and being struck by the lyrics, “With all the thinkin’ you’ve been doin’ / You could be another Lincoln / If you only had a brain.” I may have divided the lines in the wrong place, but that was where the pauses seemed to be in the song. In any case, it was obvious that the “G-dropped” version of “thinking” and “Lincoln” were supposed to rhyme, and they did—with KIT-type vowels in their weak syllables. Maybe this was a result of vowel harmony, but I think it suggests that at least some speakers probably had the modern system in 1939.

I definitely feel that /tɹ/ and /dɹ/ are underlyingly /tʃɹ/ and /dʒɹ/ for me, although I don’t notice much of a phonetic difference between speakers who feel that way and those who identify the affricates with underlying /tɹ/ and /dɹ/. The difference seems to be phonological more than phonetic; I would guess that many /tɹ/ and /dɹ/ speakers have some degree of affrication, and even for /tʃɹ/ and /dʒɹ/ speakers, the affrication is not as extreme as the symbols would suggest. The fricative element in “train” and “drain” is much shorter than in “chain” and “Jane,” even though “train” and “drain” have underlying /tʃɹ/ and /dʒɹ/. I assume this has something to do with the presence of the /ɹ/, and perhaps this length difference is why dictionaries are reluctant to recognize it. However, if a phonetic change occurred, such as /tʃ/ –> [ɧ] (just to give an arbitrary example, though this would be extremely unlikely) and /tɹ/ changed as well, then it would have to be recognized as underlyingly /tʃɹ/.

My /ɹ/ certainly matches the “bunched-tongue” descriptions in your other post, and I’ heard Americans in older films (as well as Brits) use varieties of /ɹ/ that are not bunched. It seems that some sort of clear retroflex articulation is used in the southwestern part of Britain, even after vowels. I rarely hear that sort of accent (and only from U.K. films and TV), but such an /ɹ/ sound seems quite foreign to me (as does the Lancashire /ɹ/ described in your post). Some people claim that Americans use a retroflex /ɹ/, but if any of them do, it must be much darker than the West Country /ɹ/. I suspect that most of us use a bunched /ɹ/, though, and the tongue retraction explains the Mary-merry-marry, mirror-nearer, and hurry-furry mergers. I don’t have those mergers, probably due to New York influence (my mom is originally from there), but I think most Americans have complete tense-lax neutralization before /ɹ/, probably because the /ɹ/ is often so bunched that it’s difficult to discern the nature of the preceding vowel. I also find it strange that lip-rounding is rarely mentioned for /ɹ/, even though most Americans and at least some Brits seem to have it prevocalically. I don’t have any noticeable rounding for syllable-final /ɹ/ unless placing extreme emphasis on a word that contains it (and of course, most Brits don’t have true syllable-final /ɹ/ at all—even though Wells claims linking r counts in “more ice” and similar phrases. An SSB “more ice” sounds nothing like an American “more ice” because—aside from the absence of Canadian raising—there’s no r-coloring in the vowel of SSB “more” in any position, although Daniel Jones-era RP speakers often seem to have r-coloring of the vowel in linking-r environments.)

Speaking of mergers before /ɹ/, I doubt this relates to tense-lax neutralization, but (as you can probably guess by now) I have START in historic LOT + /ɹ/ words (e.g., forest, orange, horrible) rather than NORTH. This is definitely a regionalism today, and I unconsciously tend to switch to NORTH in these words when conversing with GenAm speakers because of their typical reactions to hearing START where they expect NORTH. Of course, they have no idea that by readily being able to use either START or NORTH in LOT + /ɹ/ words, I effectively have three underlying phonemes that map to two surface phonemes. I would guess that some British northerners probably have something similar in BATH words, given that BATH=TRAP in the north of England but has the PALM/START vowel in the south. (And if I’m not mistaken, TRAP=BATH=PALM is often found in Scotland, which is another matter entirely). I wanted to mention this in particular because I noticed that you used TRAP in “after” in your “Intrusive R” video, although I think I’ve heard PALM in the same word in some other video. Do you have BATH as an underlyingly distinct phoneme that can be realized with either the TRAP vowel or the PALM vowel?

Anyway, thank you so much for responding! I’m surprised that the American “schwa split” is so widely known, given that it’s rarely discussed and dictionaries certainly don’t bother to note it. I suppose it’s yet another area in which the usual transcriptions don’t accord with the way the accent is actually spoken.

“With the thoughts you’d be thinkin’ / You could be another Lincoln” is the lyric, if anyone was confused by the apparently bizarre rhyme scheme. And yes, Judy Garland does pronounce those two to rhyme, which I’d definitely never do with my mostly SSB accent.

Such a practice seems to be traced back to Kenyon (1924) American Pronunciation (1st Ed) (available at HathiTrust), pp. 84-85; 104-105, where he admittedly noted that the American ʌ and in ə were “virtually alike except in stress”, so Kenyon knew that the two had (almost?) merged for some, if not many, Americans back in 1924, yet still chose to maintain that ʌ was exclusively stressed and ə was exclusively unstressed, which was replicated in the 6th Ed (1940) of the same book (available at Internet Archive), p. 28. I could not find his reasons for doing so. It was possibly followed by Kenyon & Knott Dictionary, which was very influential and became a widely accepted fossil!

It is peculiar that while American lexicographers have tended to establish a different-from-British tradition, in this regard many of them have chosen to stick to the British way

The fact, ʌ and ə are very different in RP, SSB, Australian English and most of USA. A reduced ʌ may overlap with ə, but this is quite the exception.

Hello; I’m an American from Metro Detroit, and I was actually initially quite surprised upon watching your video on this subject that most Americans cannot distinguish between the STRUT and COMMA vowels, as they are quite distinct to me. At first I thought that this may have been caused by a large exposure to British English as a child, but I think it’s actually more likely that American English speakers with the Northern Cities Vowel Shift (NCVS) have a significant distinction between the STRUT and COMMA vowels.

The STRUT vowel moves towards the back of the mouth in NCVS, and this seems to me to be true for both stressed and unstressed usage. In contrast, the COMMA schwa, remains in the center of the mouth. “Undone” to me is thus very much /ʌndʌn/ and definitely not /əndʌn/. To someone from Britain, a NCVS-influenced pronunciation might potentially sound more like /ɔndɔn/ though. There is no STRUT-CAUGHT merger though, since both CAUGHT and COT move forwards (also avoiding a COT-CAUGHT merger).

While this is dialectical and not General American, I think that it’s still relatively interesting, since the NCVS is a relatively recent phenomenon, and the areas that are affected by it would’ve been populated primarily by speakers with a COMMA-STRUT merger in the past. I think that STRUT-backing is becoming more common as NCVS spreads and intensifies, which would mean that the COMMA-STRUT split is a growing phenomenon in American English. Is it truly the time to remove ʌ/ə distinctions in American phonemic representations if a potentially growing part of the population is distinguishing them?

Something I forgot to emphasize in my previous comment:

If a possibly growing amount of Americans are able to develop an unconscious ability to distinguish between the STRUT and COMMA vowels in a way following pre-merger patterns, without any kind of intentional training, had STRUT and COMMA truly ever become allophonized in the first place?

I have no formal linguistic training and have no clue how common it is for 2 vowels to become allophones and then split again, following the same patterns that they had before becoming allophones. In the case of the NCVS though, I guess that influence from far-away dialects could have provided unconscious guidance on how to split the vowels though, as immigration is often proposed as a reason why a region speaking a very generic “standard American” dialect could wind up undergoing the NCVS.

In a poetry class I took in college, we learned that English has 4 levels of stress. Obviously this was more meant for decoding syllabic stress in the context of metered poetry, but for an example like “vulnerable” I would say that “vul” is a 2 or a 3 (rather than a 4 perse) and “er” “a” and “ble” are all 1s.

Thank you for sharing your insight!