Accent of evil

Two posts ago I discussed the rise of modern popular culture during the first part of the 20th century. I argued that it was phonetically influenced by three non-rhotic accent types: 1. Northeastern US, 2. Southern/African American, and to some extent 3. the British Empire’s ‘Received Pronunciation’. I described how the first of these became marginalized, as it was in the democratic nature of popular culture that the majority accent, General American, came to predominate in the USA.

Two posts ago I discussed the rise of modern popular culture during the first part of the 20th century. I argued that it was phonetically influenced by three non-rhotic accent types: 1. Northeastern US, 2. Southern/African American, and to some extent 3. the British Empire’s ‘Received Pronunciation’. I described how the first of these became marginalized, as it was in the democratic nature of popular culture that the majority accent, General American, came to predominate in the USA.

In the following post, I went on to consider the special case of popular music, where Southern/African American pronunciation continues to exert influence throughout the English-speaking world.

Today I want to consider the status of the third accent, RP, in popular culture. In particular, the widespread and often discussed idea that British or English speech is associated with evil.

An article in the Independent from 2010 begins:

From middle earth to a galaxy far far away, there exists a truth universal since the dawn of Hollywood time: bad guys speak with British accents. But it is a truth that British actress Dame Helen Mirren has become fed up with.

Speaking at an event in Los Angeles to celebrate British success in Hollywood, Dame Helen said British actors were an “easy target”. “I think it’s rather unfortunate that the villain in every movie is always British,” she said.

When people make this claim, the sort of thing they mention is George Sanders as the villainous tiger Shere Khan in Disney’s Jungle Book:

Or Steven Berkoff’s smuggling art dealer in Beverly Hills Cop:

Or Jeremy Irons’ villainous lion Scar in Disney’s Lion King:

Or Benedict Cumberbatch’s super-villain Khan in Star Trek Into Darkness:

Many writers have tried to explain this phenomenon – I think wrongly – in terms of historical American resentment towards Britain. In a Daily Mail article Barry Norman, for decades the BBC’s main film critic, wrote: “Americans have a brooding resentment of the lordly way we used to rule our colonies there”. And an older online article on the BBC’s h2g2 site claims that “the concept of the British as the ‘old masters’ and British influence as an unjust yoke to be thrown off is deeply ingrained in American cultural history”.

It’s worth pointing out that these writers aren’t very accurate about the accents they’re describing. According to the BBC article, “Beginning with Errol Flynn’s classic portrayal… Hollywood Robin Hoods have had American accents”. But the Australian Errol did not have an American accent. Here he is exhibiting BATH-broadening, non-rhoticity and a generally British vowel system in I’ll get myself a staff… What else d’you call a man who takes advantage of the King’s misfortune to seize his power?

And both the Independent and Mail articles claim that Anthony Hopkins played the villainous Hannibal Lecter with an English accent. Again, false. Hopkins is clearly Southern USA in his famous first scene with Jodie Foster’s agent Starling (Closer… from the student body… That is the Duomo seen from the Belvedere):

Elsewhere he’s occasionally rhotic, generally lacks BATH-broadening, has unrounded LOT. Not an English accent.

More importantly, the writers are missing the main point by thinking in national terms – filmmakers from one nation, the USA, supposedly choosing actors on the basis of negative feelings about another nation, Britain. I think the primary factor is social rather than national: the most important thing about ‘British villains’ is not their country of origin but the fact that they sound upper class.

This was vividly demonstrated earlier this year when Jaguar, the Indian-owned British luxury car manufacturer, launched a lavish TV campaign to around 90 million viewers during the Super Bowl, America’s annual football championship game. Starring Tom Hiddleston, Sir Ben Kingsley and Mark Strong, and directed by Tom Hooper of The King’s Speech, the ad begins “Have you ever noticed how in Hollywood movies all the villains are played by Brits? Maybe we just sound right…” A helicopter races a Jaguar around famous London tourist spots while the British stars tells us, tongue in cheek, that “we’re more focused, more precise… we’re always one step ahead… we’re obsessed by power… and we all drive Jaguars. Oh yes, it’s good to be bad.”

Jaguar 2014 Big Game Commercial British Villains Rendezvous Jaguar USA

Enjoy the videos and music you love, upload original content, and share it all with friends, family, and the world on YouTube.

The Jaguar campaign helps us to understand the perception of this type of accent in the English speaking world, though it’s worded in the same national terms (“Brits”) as before. We have to grasp two things. On the one hand, the accent at the heart of the matter is not any British accent but Received Pronunciation, the accent of the British empire’s ruling elite. RP, as I put it in another post, was from its very conception the accent of privilege. On the other hand, modern post-imperial culture places value on democracy and equality, which dovetail with traditional values like compassion for the poor and disadvantaged; a corollary of this has been the stigmatization of privilege. In storytelling, audiences sympathize and identify with the ordinary, the humble and the vulnerable more than with the privileged and the wealthy.

So RP-type speech is a good choice for evoking elitist associations in adverts, appealing to consumers who want to demonstrate their wealth and high class tastes. But it’s easier for a Jaguar to pass through the eye of a needle than for an audience to empathize with an unfairly advantaged character, especially one who flaunts their status. Materialistically, we may envy the trappings; but morally, these trappings (including the accent) are associated with being bad.

Of course not all villains speak RP. We’ve already seen that Anthony Hopkins’ Hannibal Lecter was not RP-speaking; besides, the real villain of The Silence of the Lambs is the serial killer ‘Buffalo Bill’, an American played by an American. Many of the most iconic villains are American, especially when the villainy comes not from privilege but from mental disturbance or social marginalization: Psycho‘s Norman Bates (and various other slashers), Robert Mitchum’s psychopaths in Cape Fear and The Night of the Hunter, assorted Dennis Hopper villains, Batman’s nemesis the Joker, Jack Nicholson in The Shining and Kathy Bates in Misery, and any number of manipulative femmes fatales and Italian-American gangsters.

And not all RP-speakers are villains. The accent’s eliteness is sometimes exploited for non-evil connotations, such as benign seniority. Think of Obi-Wan Kenobi as portrayed by Sir Alec Guinness in Star Wars or Sir Patrick Stewart’s captain on the generally American-speaking starship Enterprise. Another niche of potentially sympathetic RP speakers are higher-ranking servants from the old days, like Jeeves and Mary Poppins, or Batman’s butler Alfred.

Further, British characters who don’t speak RP are often sympathetic. James Bond conquered the world (including the US) in the Scottish-accented form of Sean Connery. A London accent is similarly free of villainous baggage, whether real, like Michael Caine’s, or preposterous, like Dick Van Dyke’s. Some years ago American car insurer GEICO decided that the animated gecko in their TV ads should switch from RP to Cockney, as discussed on Language Log. (Only the elite drive Jaguars, but everyone needs car insurance.)

So it’s not Britishness but classiness that causes the problems. Villains often like classical music, and RP is the phonetic equivalent.

The clinching evidence that it’s about class rather than nationality is this: the same associations of RP apply within Britain.

Every Christmas season, British theatres are given over to pantomime, panto for short. Pantos are musical comedy fantasies based on traditional children’s stories, including Snow White, Cinderella, Aladdin, Babes in the Wood, Dick Whittington, Peter Pan. Usually, these stories feature a young, humble and/or disadvantaged hero or heroine struggling against a grand, older, powerful and often titled villain, such as a wicked queen or wizard, King Rat, etc. In panto it’s normal for the performers to have regional accents – except for the villain, who of course speaks RP. In this brief and amusing ad for a production of Aladdin in Glasgow, three of the four performers (hero, genie, and cross-dressing ‘dame’) have Scottish accents, while the villain Abanazar speaks RP:

King’s Theatre Glasgow 2013 pantomime Aladdin

To buy tickets visit… http://www.atgtickets.com/shows/aladdin/kings-theatre/ We’re delighted to announce that we are reuniting the cast from last year’s cr…

In this panto from Basildon, Essex, an Estuary-ish dame interacts with a Captain Hook whose RP has a posh old æ vowel (starting 3:25):

It’s Smee…! Pantomime Dame-Peter Pan

Mrs Smee – opening routine – Peter Pan at the Towngate Theatre, Basildon – 2012/13. (Featuring Bryan Torfeh as Captain Hook)

So, just like Americans, Brits associate grand villainy with upmarket accents. The very British cast of the Harry Potter films includes quite a few upmarket speakers, but outclassing the rest as megalomaniac-snob-racist Lord [sic] Voldemort is Ralph Nathaniel Twisleton-Wykeham-Fiennes, eighth cousin of the Prince of Wales:

Note for example Fiennes’ æ in Harry and the backish first element of proud, now posh and old-fashioned.

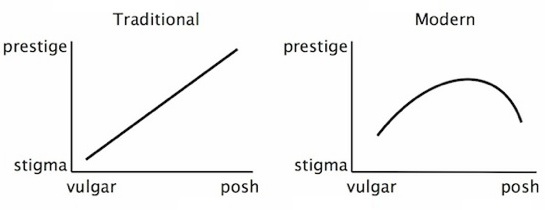

Poshness and old-fashionedness go hand in hand because of sociophonetic change in Britain/England over the last half century. Traditionally, as I explained in an earlier post, there was a fairly straightforward, linear relation between social class and prestige, but changes in social attitudes – which can’t simply be attributed to Hollywood – had the effect of stigmatizing privilege. Crudely: With their growing stigmatization, posh accents became increasingly marginal in the British mass media which they formerly dominated. By 1982 John Wells had to invoke the concept of ‘U-RP’, i.e. RP posh enough to carry negative associations. The typical speakers he suggested were amusing stereotypes, such as the dowager duchess and the elderly Oxbridge don; at least one, the Terry-Thomas cad, counts as a villain. Increasingly it became the role of posher speakers to be laughed at and/or vanquished.

With their growing stigmatization, posh accents became increasingly marginal in the British mass media which they formerly dominated. By 1982 John Wells had to invoke the concept of ‘U-RP’, i.e. RP posh enough to carry negative associations. The typical speakers he suggested were amusing stereotypes, such as the dowager duchess and the elderly Oxbridge don; at least one, the Terry-Thomas cad, counts as a villain. Increasingly it became the role of posher speakers to be laughed at and/or vanquished.

(The clip of King Rat and dame above nicely shows how villains are there not merely to be defeated but also to be deflated. This mockery can even be self-directed, as it often was by Noël Coward; in their different ways Stephen Fry, Hugh Grant and Boris Johnson gained popularity playing their poshness comedically.)

The character of Sherlock Holmes is interesting in this regard. Though a crimefighter, Holmes has several of the characteristics of a villain, including withering haughtiness, a violin and a drug habit. He’s been notably portrayed by stars who often played villains, like Basil Rathbone and Peter Cushing. Audiences empathize more with Holmes’s more human sidekick Dr Watson, and recent Watsons have been given less posh, more ‘contemporary’ personas and accents – Jude Law on the big screen, Martin Freeman on TV. Compared with Freeman, Benedict Cumberbatch – who’s also made ads for Jaguar – has a closer FACE vowel and opener THOUGHT, and he occasionally likes to use a geunine iː in FLEECE (send your least irritating officers and an ambulance… to lead others to peace in a world at war):

It’s therefore unsurprising that in the epic Hobbit films Martin Freeman plays the hero while the posher Cumberbatch plays the villain.

Which brings us back to the national question. The Hobbit films are obviously set not in Britain, but in some supranational anglosphere. And the traditional status of RP, a product of the empire’s heyday was supranational. RP was often defined as being crucially unspecific as to the origins of its speaker, who might be from Surrey, Inverness, Vancouver or Rhodesia. The term ‘Received Pronunciation’ contained no reference to its nationality: it was simply the respectable way to pronounce the English language.

The semiotics of RP have continued to function throughout the ‘inner circle’ of the English-speaking world, mother country and ex-colonies alike. Those ex-colonies had flatter social structures and lacked distinct upper classes of their own, so the empire’s elite accent continued to symbolize a social pinnacle everywhere. Even in long-independent America, a sign of the lingering aura of RP was the old stage accent sometimes known as ‘American Theater Standard’ — an Americanized RP which implicitly deferred to the elite status of the old country’s ruling accent.

Hollywood bore no grudge against the British. On the contrary, Hollywood has been unstintingly hospitable to British talent from Charlie Chaplin to the present day. But Hollywood, like British panto, has always favoured stories which pit underdogs against overdogs. For those overdogs it has consistently acknowledged and exploited the most elite accent of the anglosphere: RP.

It has become an international stylistic trope, not unlike the international adoption of American accents for pop/rock singing. In popular culture, performers who approximate RP are tapping into a range of associations that include old-fashionedness, seniority, cultivation, traditional manners, expensive education and tastes, haughtiness, smugness, pomposity and, in many narrative contexts, evil.