The fallac[ɪj]of schwee

In a recent blog post, John Wells returned to the topic of the happY vowel and the symbol i, often nicknamed “schwee”. He began rather plaintively:

In a recent blog post, John Wells returned to the topic of the happY vowel and the symbol i, often nicknamed “schwee”. He began rather plaintively:

Indeed, though widely adopted in dictionaries and textbooks, schwee has caused widespread confusion ever since it was invented. In this post I’ll try to clear up the most common misinterpretations. Further, I’ll show that even if it’s interpreted correctly, it serves no useful purpose in describing contemporary standard pronunciation. The CUBE dictionary which I co-edit has never bothered to use it.

Here is John Wells’s explanation of the basic concept in an earlier post:

In 1978, John tells us, “pronunciation editor Gordon Walsh introduced the additional symbol i, to cover such cases”. John emphasizes that this additional symbol is an “abbreviatory notational convention”, standing for two equally recommendable alternative possibilities – and not a third vowel in addition to FLEECE and KIT:

happy ˈhæpɪ, ˈhæpiː

valley ˈvælɪ, ˈvæliː

happy ˈhæpi

valley ˈvæli

As John points out, the history of phonological theory has a more technical term for this kind of thing: “Trubetzkoy would have spoken of the iː ~ ɪ archiphoneme”. In simpler terms, schwee as originally intended is not a vowel at all, but a disjunction of two vowels: FLEECE or KIT. It doesn’t have a pronunciation – it stands for two alternative pronunciations.

People with a bit of phonetic training will have heard of phonemes and allophones, but not archiphonemes. So it’s unsurprising that schwee has been misinterpreted in two main ways: either as a phoneme, or as an allophone.

Both these misinterpretations have taken hold at various academic levels. I recently gave a talk at Middlesex University, where I found that excellent students of English & TEFL had made the phonemic misinterpretation. That is, they thought that English has three close front unrounded vowels, namely FLEECE, KIT and (whether they know the nickname or not) schwee. This is not merely untrue of English; unless I’m mistaken, I don’t think any human language contrasts three close front unrounded vowels.

This picture of three different vowels can even be found in publications, like this textbook aimed at Dutch teachers of English (English pronunciation for student teachers, Noordhoff Uitgevers, 1997):

Note the use of slanting brackets for all three, giving the impression that “/i/” is a phoneme like the other two, with various allophonic realizations, such as [ɪ]. Let me point out that the authors, Carlos Gussenhoven and Ton Broeders, are not only scholars of the first rank and awesomely native-sounding speakers of English, they’re also my erstwhile employers (I’m one of the native speakers on this textbook’s accompanying CD). I’m certain there are no better teachers of English pronunciation for Dutch speakers; but “/i/” as they present it is not Wells’s “abbreviatory notational convention”, and clearly implies that English exemplifies what I suspect is a phonological impossibility.

Let’s turn now to the allophonic misinterpretation — that “i” means a precise specification of how the final vowel in happy should be pronounced, namely as a short close front vowel [i]. I’ve heard with my own ears professional academic phoneticians teaching this misinterpretation to their students. Now it’s perfectly true that many speakers often realize the underlined vowels of happy and mediocre as a short close front vowel [i]. But dictionaries don’t generally introduce special symbols to show fine, sub-phonemic details, such as aspiration. All vowels exhibit allophonic variation, often quite drastic: listen to the GOAT vowel being given very different pronunciations in the stressed and unstressed syllables of low and yellow (Macmillan online dictionary):

Those pronunciations are very different, but dictionaries don’t show the difference by inflicting an extra symbol on their users, say /əʊ/ for the vowel in low and /o/ for the vowel in yellow. And yet that’s exactly what most dictionaries do for the vowels in key and monkey.

Another, more important, objection to the allophonic misinterpretation is that [i] is certainly not the only way to pronounce the final vowel in happy: we frequently hear pronunciations with exactly the same quality and quantity as stressed FLEECE. Here’s BBC newsreader Kasia Madera saying party with a final vowel which I would transcribe narrowly as [ɪj] rather than [i]:

And here is Prince William making a speech in Nottingham last week, in which his final vowel of opportunity, majesty, tirelessly, charity, particularly, country is the same one he’d use in tea, lee and tree:

Some older RP speakers (including John himself, b. 1939) still have KIT /ɪ/ in happy and coffee, but this was already sounding old-fashioned in the 1980s, and today it’s frankly absurd to suggest to learners that opportunity, charity etc. should be pronounced in some way that’s different from the FLEECE vowel.

It’s worth pointing out to my non-native readers just how comical the /ɪ/ pronunciation now sounds to native Brits in words like quality, vitality and family, from old information films and the Queen’s 1957 Christmas broadcast:

(In the second clip there we hear happY encroaching on the RP DRESS vowel [e̞]. Schwee hobbyists shouldn’t miss Jack Windsor Lewis’s discussion here of a variety of old happYs.)

The [ɪ] pronunciation is still used in some regional accents. Here is Lancashire comedian Peter Kay saying there were a guy in t’toilets collared me (= there was a guy in the toilets who stopped me) and very weird:

There we hear KIT in both the unstressed pronoun me and finally in very. But in standard BrE, happy=FLEECE now predominates.

And this brings us back to Wells’s original schwee, the abbreviatory archiphoneme which stands for unstressed FLEECE or KIT. When it was first used in the 1970s, there was at least some justification for abbreviating ˈkɒfɪ, ˈkɒfiː to coffee ˈkɒfi, because the two alternatives were equally recommendable. But this is simply no longer the case. In any given phonetic environment, either FLEECE and KIT are contrastive, or else one is predominant and recommendable, while the other is dated or a regionalism. And with the loss of contexts in which FLEECE and KIT are equally acceptable, the raison d’etre for the abbreviation i is also lost.

On the contrary, the FLEECE-KIT distinction carries an immense functional load; one has only to think of pairs like sheet-shit, beach-bitch and peace-piss. And for most learners of English, this contrast is very hard to perceive and to produce: in teaching, therefore, the distinction should be prioritized and insisted upon. Encouraging learners to think of FLEECE and KIT as neutralizable, while burdening them with a non-existent third phoneme, is pedagogical nonsense. If BrE were being analyzed and transcribed for the first time today, I doubt that any linguist would use schwee: as John Wells made clear in his blog, it was only invented as a sop to the obsolescent happy=KIT pronunciation, preserving it alongside the new standard happy=FLEECE.

In stressed syllables, the FLEECE and KIT vowels ɪj and ɪ are contrastive and have to be learned word by word. (The orthography provides guidance, as in fleece and kit, although there are some tricky cases like mini with ɪ versus linguine with ɪj.) For unstressed syllables, the basic rule is simple:

• if a consonant follows, ɪ (ə for some speakers/accents)

• if not, ɪj

Let’s go through some examples. First, inital unstressed syllables:

retain, menagerie, beneath, fidelity, prefer, divine, enough

• if not, ɪj:

create, meander, beatify, fiesta, preoccupy, viola

Distinct from these unstressed syllables are the stressed “word-level” prefixes, re-, pre– and de-. These have transparent meanings, can be added to words rather freely and are sometimes written with a hyphen. They have FLEECE even if a consonant follows, unlike the unstressed “root-level” prefixes with the same spelling which do not have transparent meanings and cannot be freely added:

pre- ‘previously’ e.g. ˌprɪjˈowned ˌprɪjˈcooked (compare prɪˈfer)

de- ‘undo’ e.g. ˌdɪjˈactivate ˌdɪjˈpressurize (compare dɪˈcide)

Moving on to medial syllables, here are examples before the primary stress:

irrigation, elevation, animosity, California

• if not, ɪj:

variation, permeation, grandiosity, Riviera

And medial syllables after the primary stress:

telescope, caffeinated, aniseed, audible

• if not, ɪj:

deviate, radiator, lineage, audio

Lastly, we come to final syllables.

coffin, trumpet, minute, porridge, ragged

• if not, ɪj:coffee, mini, chimney, twenty, rally

Traditional RP’s use of KIT in absolute final position was rather anomalous, since English generally allows short-lax vowels only before consonants. RP made exceptions to this generalization in allowing unstressed KIT and FOOT to occur finally, as in happy ˈhæpɪ and thank you ˈθæŋkjʊ – neither of them extinct, but both of them now old-fashioned and not very recommendable to learners, who tend to be young. We can now see that modern BrE has regularized the system by shedding these forms, so that none of the English short vowels, except final unstressed schwa, may occur without a following consonant.

Where KIT occurs in unstressed syllables, some speakers/accents use schwa, or an intermediate quality like [ɨ]. This is true of many Americans, but also some BrE speakers. In the following samples, former Prime Minister Tony Blair exhibits such schwa-like qualities in regarded, activated and minutes:

Note that this is not possible in absolute final position: whereas happɪ is merely old-fashioned, happə is out of the question. I take this as confirmation that, when no consonant follows, the contemporary language chooses the FLEECE option, not the KIT/schwa option.

Finally, there are some apparent exceptions to the Unstressed FLEECE/KIT Rule, but these fall into two systematic categories. One category arises when word-formation processes attach a further consonant to a word-final unstressed ɪj. For example, if we add the inflectional endings –s or –ed to pity or rally, we get pities, rallies, pitied, rallied. In these words many speakers keep the FLEECE vowel even though it’s now preconsonantal. Here, for example, is the BBC’s Jeremy Paxman saying our most elite universities:

So for many speakers, there’s a difference between pitied pɪtɪj+d and pitted pɪt+ɪd, between rallied ralɪj+d and valid valɪd. Other speakers, however, conform more fully to the Unstressed FLEECE/KIT Rule by switching from FLEECE to KIT when a consonant is attached to the end of the word. Both kinds of speaker work for Sky Movies:

(A similar variability applies to the -(e)y in compounds like bellydancer and chimneysweep, the portmanteau gerrymander, and also poly when it’s used as a productive word-level prefix transparently meaning ‘many’, eg polysyllabic, polymath. Cf polythene, which definitely has KIT and not FLEECE.)

Another category of apparent exception is illustrated by words like chlorine, athlete, phoneme, species, colleague, caffeine. The underlined vowels contain FLEECE despite a following consonant, within the same morpheme. However, these can be analyzed as containing a secondary stress: ˈchloˌrine, ˈathˌlete, etc. Such an analysis is supported by words such as ˌchloriˈnation and ˌdeˌcaffeiˈnation, where the underlined vowels find themselves between two stressed syllables and become fully unstressed; as a result, they switch from FLEECE to KIT and thus conform to the Unstressed FLEECE/KIT Rule.

To summarize. A phonemic misinterpretation of schwee is wrong because schwee isn’t contrastive, and because it implies a linguistically odd triple set of high front unrounded vowels. An allophonic misinterpretation of schwee is inappropriate for broad transcription, and makes no allowance for realizations other than [i]. Schwee in its authentic, archiphonemic interpretation was justified to the extent that unstressed FLEECE and KIT were equal alternatives in certain contexts; in contemporary BrE, however, the distribution of unstressed FLEECE and KIT has been regularized – KIT before a consonant, FLEECE elsewhere – so that archiphonemic schwee obscures valid generalizations and recommends inadvisable pronunciations.

All of these interpretations involve an addition to the list of English vowel symbols, with schwee generally accompanied by its even weirder sister schwoo, u. (In a nutshell, schwoo gives a common description to the middle vowel of occupy and the first vowel of fruition, the implication being that both can equally be GOOSE or FOOT. Whether or not this was true of RP, it doesn’t match what I tend to hear in BrE today, namely schwa in preconsonantal forms like occupy and GOOSE elsewhere.)

Some readers will feel that schwee is a familiar symbol which does no harm. But the English vowel system is large and difficult enough without adding extra symbols, and we should keep future learners in mind. Carlos and Ton’s Dutch readers at least have the advantage of coming from a first language with a large and difficult vowel system – Dutch has almost as many vowels as RP. But think of, say, Spanish speakers. For every one of their five native vowels, the RP system confronts them with four. (If you’ve studied the piano, imagine encountering a new keyboard where each octave is divided not into twelve keys but forty-eight.) English vowels are a huge challenge, and I think we should take every opportunity to economize and prioritize.

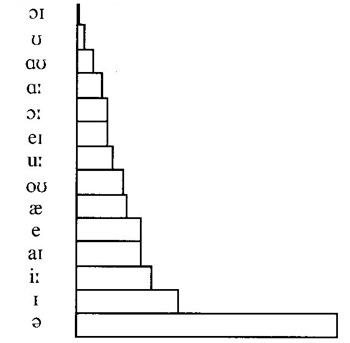

Here is a chart of vowel frequency (in AmE) from Ladefoged and Disner’s Vowels and Consonants:

The prevalence of schwa, KIT and FLEECE is attributable to their being the three vowels which occur in unstressed as well as stressed syllables (ə here also includes stressed STRUT vowels; a proportion of unstressed ə tokens here would probably come under ɪ in BrE). To me, this chart suggests that anyone who wants to sound like a native English speaker needs to prioritize these three vowels – their perception, their production and their distribution. How much are learners helped by relegating “weak vowels” to a secondary group containing additional symbols which actually obscure and/or confuse the differences between them?

The prevalence of schwa, KIT and FLEECE is attributable to their being the three vowels which occur in unstressed as well as stressed syllables (ə here also includes stressed STRUT vowels; a proportion of unstressed ə tokens here would probably come under ɪ in BrE). To me, this chart suggests that anyone who wants to sound like a native English speaker needs to prioritize these three vowels – their perception, their production and their distribution. How much are learners helped by relegating “weak vowels” to a secondary group containing additional symbols which actually obscure and/or confuse the differences between them?

Of course a “polysystemic” view of vowels in stress languages is well motivated. Many languages have diminished vowel possibilities in unstressed syllables. Russian, for example, has both e and i in stressed syllables, but only i in unstressed syllables. In BrE, ɪj and ɪ freely contrast in stressed syllables, while in each unstressed environment one is pr[ɪ]ferred over th[ɪj]other. The question is whether it makes sense to describe a decrease in phonetic possibilities by means of an increase in the vowel inventory. I tend to think twent[ɪj]is more than [ɪ]nough.